REMOTE JURY SELECTION DURING A PANDEMIC

Jack Tuter, Chief Judge 17th Judicial Circuit, State of Florida

The 2020 Covid-19 pandemic is not the first-time courts have shut down. In the early part of this century, the “Spanish-flu” wreaked havoc on this country and the third branch of government.

While pandemics vary in severity, the pandemic of 1918, sometimes termed the “Spanish flu,” is generally regarded as the most deadly disease event in human history, killing over 40 million people in less than a year. This 1918 pandemic also had another notable characteristic: while most deaths from influenza occur in the very young or very old, the deaths from this pandemic were primarily in those aged 15–35, with 99% of deaths in those under 65. Pandemic Influenza Bench Guide, 2019 Edition

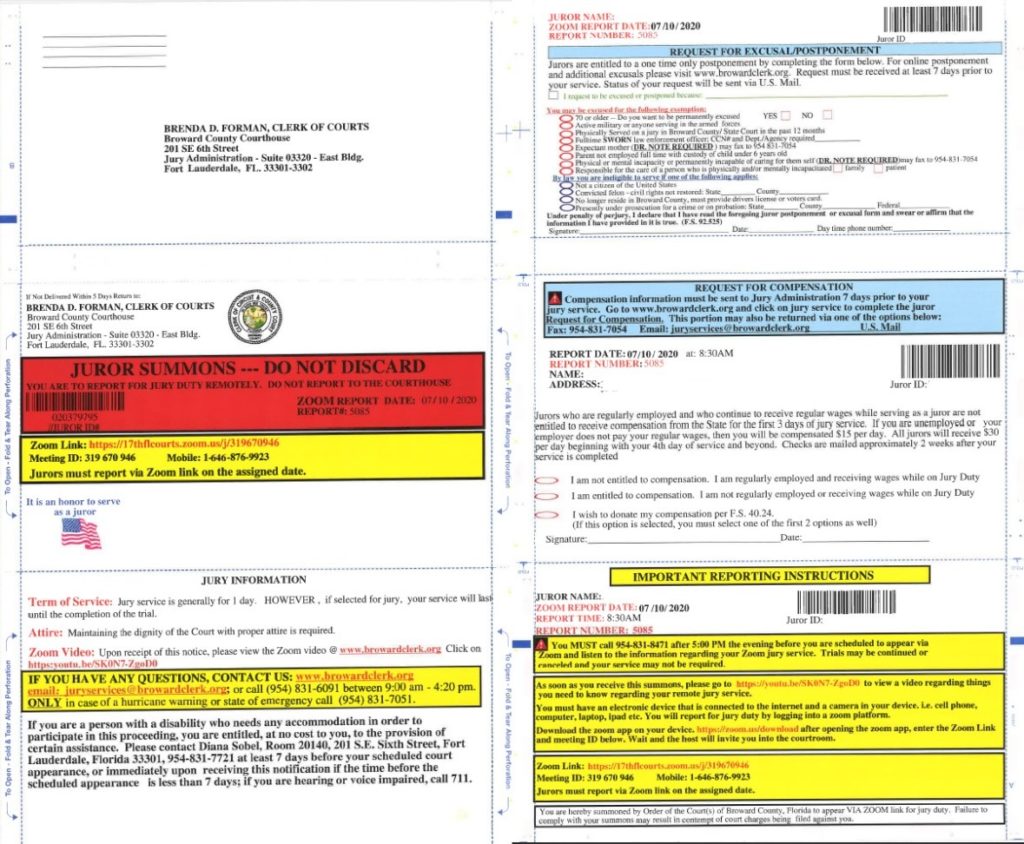

In the latter part of June 2020, 120 prospective jurors residing in Broward County, Florida, received a summons for jury duty. Like all summons in Florida, the prospective jurors received their notices for jury duty in the mail and were selected randomly by a computer using the Florida driver’s license data base.

The summons, a first in Florida, instructed the panel of jurors to report for jury duty over the Internet. The juror summons was modified with specific directions not to come to the courthouse. Happily, only one juror appeared in the juror parking lot. Forty-nine other jurors promptly reported at 8:30 am by connecting to a Zoom platform. Another 4-6 jurors had been previously excused. In total 55 of 120 jurors answered the call to duty. (A similar experiment is in process pursuant to an order by a workgroup appointed by Chief Justice Charles Canaday of the Florida Supreme Court).

Except for specific instructions as to how to report for jury duty, the juror summons was not altered. The summons instructed jurors to report at 8:30 a.m., July 10, 2020. The summons specifically instructed jurors to go to a website and view a video which gave instructions on how to check-in for jury duty; instructions to go to the Zoom website and download the Zoom app; and lastly, the juror was told to go to the 17th Circuit website, find the name of the Chief Judge and obtain the log-in information for the judges Zoom platform. None of the 49 jurors who checked in for jury duty could have done so unless they followed all of these instructions. The success rate was a true testament of faith in the jury system.

The presiding Judge, (Patti Henning), was joined for the 8:30 a.m. check-in by two members of the Broward County Clerk of Court’s jury staff and a member of the Court’s Judicial Information System staff.

It had been pre-determined that only 20-25 jurors would be needed for voir dire to keep the process as concise as possible. It was abundantly clear at the outset that pre-selection of a panel would be more tedious than expected. First, everyone had to check-in remotely and had to be asked about their right to compensation for serving as jurors. Next the presiding judge had to go through juror exemptions, juror hardships, and juror equipment to be used during jury selection. The check-in process lasted one hour and fifteen minutes.

Some jurors expressed difficulty with operating video equipment primarily with the use of iPhones. Some stated they could only view four video panels on Zoom and felt uncomfortable participating; others claimed weak Wi-Fi signals; some made excuses just to bail out such as being at a car repair shop when they checked in.

Despite the aforementioned, everyone who observed this experiment thought the prospective jurors wanted to participate and were fully engaged throughout the process. Once a panel was pre-screened down to 23, the jurors were brought into the virtual courtroom where abbreviated jury instructions were read and voir dire began.

Because Zoom does not permit “tiles” to be moved, jurors were numbered 1-23 for ease of locating the jurors on the screen. A group of attorneys from the American Board of Trial Advocates conducted the voir dire and used a negligence case from which to ask questions. It had been pre-planned by the attorneys and court to ask questions which primarily focused on the use of a Zoom platform while serving on a jury duty. Jurors were asked to mute their microphones and raise their hands to be recognized. Overall, the jurors responded to questions posed by the attorneys as they would in any courtroom environment.

Each side was given 20-25 minutes to conduct voir dire. At the conclusion of questioning, the jury was placed in a virtual break-out room and the court and attorneys selected the jury. The jury was brought out of the break-out room and an announcement was made as to who had been chosen.

After the jury was chosen, the spectators, many of whom were judges, attorneys, and a member of the news media who engaged in a question and answer session with all 23 jurors.

The jurors were asked, “Do you feel you could participate in a jury trial and render a fair verdict if the trial was conducted completely on video?” “Would you rather attend jury duty this way as opposed to in the courthouse practicing social distancing and wearing a mask?” “Do you feel you may be distracted sitting as a juror in this format?” “Do you feel using this format you were not able to feel fully engaged in the jury selection?” “Do you feel you were limited in engaging in the process due to technology limitations i.e. Wi-Fi or equipment?” “Do you feel you may not be able to judge credibility of a witness over Zoom?” “In a personal injury case where the Plaintiff may have suffered catastrophic injuries do you feel you may not be able to award large sums of money as you may only see the injured person or their family for a limited time?”

Based on answers from the prospective panel of jurors and feedback solicited at the conclusion of the event, the following lessons were learned:

- All of the jurors felt they could comfortably participate in a remote jury trial and expressed few limitations

- Some jurors felt a Zoom jury trial had its limitations in scope i.e. some felt this would not be a good format for a serious criminal trial

- Some jurors felt slightly limited using a phone for jury service however, after the event was over, those concerns diminished

- All felt they could judge credibility over a Zoom trial

- Given the choice to serve on jury duty via Zoom or live most felt they would choose zoom however, all felt if compelled they would go to the courthouse and serve on a jury

- The juror summons instructions were clear but most did not see the instruction to fill out a juror questionnaire

- The instructional video gave clear instructions as to what they needed to do to participate in jury duty

- Everyone participating in jury selection felt they could serve on a jury via Zoom and render a fair verdict

There is no doubt in my mind jury trials can be conducted via a video platform. Had a judge brought up this possibility of viable jury trials to the legal community in March 2020 it is unlikely anyone would have thought it possible.

Today, with continued Covid-19 outbreaks, remote jury trials may be the only way to safely move cases on civil dockets. Video trials do have limitations especially in the criminal justice arena, but, certain civil cases and other non-due process cases can be tried by a jury using a video platform. The unanswered question remains whether participants will feel comfortable enough to stipulate to seating a jury and resolving their case remotely.

The legal profession is prone to centuries old-processes. As attorneys and litigants seamlessly transition into a non-face to face environment, trials conducted via a video platform offer an effective and viable alternative to face-to-face encounters in a courthouse.

The 17th Judicial Circuit conducted a series of mock jury trials and voir dire sessions. These are not part of the Chief Justice’s workgroup directives.